Reflections and Lessons Learned for Developing Online Global Studies Courses for High School Students

During the school year 2022-2023, I was a GEBG Action Research Fellow. When the GEBG Research Fellowship began, I was serving as the Director of Global Education at Felsted School, which is a 459 year old, co-educational boarding school in Essex, England. During almost nine years in that role, I was fortunate enough to run Global Studies programmes, both on campus and online for over 4,000 students from more than 40 countries, mostly during the summer.

The in-person programmes were an absolute joy to be a part of, as young people were able to engage, learn and collaborate with one another while overcoming cultural boundaries and making friends for life. They experienced what were typically higher level International Relations subjects that had been modified and redesigned to accommodate their age group while they were also able to live together, explore the UK together and bond through social activities.

Although I now work at another education organisation, I continue to believe in the value and the benefit of the initiative. If young people are going to try and solve issues relating to environmental degradation, climate migration, and the increase of fundamentalist conservatism in politics around the world, being able to collaborate in a cross-cultural capacity will be an essential attribute and skill for the future.

When the Covid Pandemic swept the world in 2020 and international travel became limited, the Global Studies programmes that my team at Felsted delivered were replaced with an online alternative. I worked alongside my esteemed colleague and collaborator, Kirsty Fraser, to ensure that the Global Studies courses we had developed over the years could be accessed by young people wherever they might be in the world and for a highly subsidised fee. At the time, Kirsty and I were both certain that the impact of these online experiments could not equal the impact of our in-person programmes, but as more students from across the world joined, we began to question this assumption.

We ran seven Global Studies programmes between July 2020 and June 2022, bringing together 2,250 students in total and creating a huge global community of young people who were interested in learning about our specialist subject areas while making new friends, sharing experiences and embracing the changes that were made to all of our lives. Even though I left Felsted in November 2022, I was still curious about how much the students in the online program learned in relation to the learning goals we had for them, and the GEBG Action Research Fellows program provided an opportunity to design an action research study to explore the topic. The goal of this action research study was to identify some ways to improve the experience of learning online and the development of student global competencies in an online setting, particularly cross-cultural communication skills, by learning more about the experiences of student participants in the 2020 programmes.

Research Design:

Instead of speaking to students who were taking part in revised and refreshed online Global Studies programmes, which had been the initial intention, I decided to engage with some of the students who took part in those first few programmes in 2020, students who were typically either in their final year of high school or their first two years of university.

These students had since had time to reflect on their experiences and think in considerable detail about how their Global Studies experiences online had impacted their lives moving forward. It was through conducting interviews and holding focus groups with these students that I was able to obtain the data and information needed to extract findings that might inform similar work in the future. The reflections that the students were able to provide were well considered, balanced and, most importantly, came from a diverse number of individuals situated all around the world, including the UK, Pakistan, Argentina, Turkey, South Africa and India.

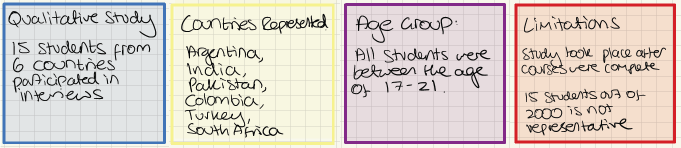

This was a qualitative study, where data was collected from 15 students from 6 countries through interviews and questionnaires. All of the students taking part were highly motivated to communicate their reflections, and although their answers were detailed and comprehensive, it is important to remember that these findings do not represent the 2,250 students who took part; the data set is just too small for that. These findings come from those students who were able to obtain the support from their parents to take part in this study and who were engaged enough to understand the value of contributing. This is a limitation of the research, though it still led to findings that may be beneficial for future programmes.

I have separated the findings into four areas. None of the findings relate to the curriculum specifically, as the subjects for each of the courses that Kirsty and I ran differed from course to course. Further research on course content would certainly be helpful moving forward, but getting the foundations of the context for study first was a priority. Quotations from students have been used throughout with permission, though first names and the initials of surnames have been used instead of full names. Countries have not been included to minimise the risk of generalisation.

Focussing on local issues helped facilitate empathetic dialogue.

“From where I stand, when we were undertaking an incredibly broad global issue such as racism, feminism or AI, it really helped to take a look at it from different local perspectives. In this way, I could really understand how a debate on one single theme could take us down different paths depending on the culture, background or religion we were analysing it from” – Victoria P.

The subjects that we tackled in the Global Studies classes (for example, “Human Rights Protection” or “The Theory and Practice of Foreign Aid”) were broad enough to appeal to young people all over the world and didn’t limit the discussions to specific geographic areas. However, we ensured that there was time for students to address local issues as well, and this had a huge impact on community building. We noticed this at the time of course, but listening to how it impacted students years later was particularly interesting. Students talked about their eagerness to discuss and learn about specific issues relating to the home countries and towns of those participating. This helped facilitate the cross-cultural dialogue that was void of the preconceived opinions formed on the basis of global headlines. It also gave the young people participating the courage to speak in relatively large classes (the largest class size was over 300 participants), and if they were speaking about a local issue that they knew well and were able to apply that to a broader topic, they felt more comfortable.

Obtaining support and buy in from a responsible adult helped with learning, confidence building and integration.

“Obtaining support from an adult during online learning, especially during the pandemic, provided crucial guidance and assistance with technical challenges, time management, and staying motivated. Their presence ensured a smoother learning experience and facilitated better engagement with the course content” – Khadijah K.

With any online learning, young people need to have the support of someone they see regularly in person so that they are able to talk through what they have learned and address any concerns that they might have about what they are studying. Of course the online teachers need to be as present and engaged as possible; when Kirsty and I ran our programmes we had a brilliant and supportive team behind us who were able to connect with any of the students who were struggling. However, speaking to some of these students years after their first course, they felt that having someone at home who had a good understanding of what they were doing, particularly from the perspective of Global Studies, was crucial. When talking through mechanisms of support with the students’ teachers, it transpired that creating subject-based sessions for parents would help. Indeed, delivering sessions just for parents was also perceived as having a hugely positive impact in parents understanding the value of cross-cultural collaboration and resulted in more discussions at home. Finding a suitable time to make this happen, though, was difficult and that meant engagement was generally quite low.

Linking skills, knowledge and experience outcomes to university and job role specifics, so students felt as though they were working towards mutually beneficial goals.

“Linking the course content to skills relevant [to future work and study] helped me establish common ground among peers. It created a shared interest in preparing for future academic endeavours, fostering connections and conversations around educational goals, aspirations, and strategies” – Sawaira A.

I experimented with linking university entry criteria onto courses related to International Relations several times during the Global Studies programmes, but I did not understand the importance of this at the time and consequently did not do it frequently enough. Students felt confident discussing career and higher education goals with each other, regardless of cultural differences, when they were able to align their interests and passions. Framing some of the course content around outcomes that could have a positive impact on enrollment and employment in the future helped increase cross-cultural dialogue, particularly when tasks involved collaboration with other students from different parts of the world.

Allow time and resources for interaction and community building outside of the lessons.

“Other resources such as discussion threads were really helpful to get the point of views or a more extensive opinion of those students who might not be really keen on expressing themselves in online lessons due to embarrassment” – Conrado T.

“I believe it was actually really helpful having the “forum”, because if I had something I couldn’t say during the lesson or wanted to add material/any reflection, I could do it freely and could read what people had to say about it. I also think it was really helpful because it was asynchronous and there was not a pressure of being connected at a certain time and therefore could be flexible with different time zones.” – Victoria P.

Students talked through the importance of having a safe space to discuss subjects that were important to them, such as music, art and other social issues that did not relate directly to the subject matter. The unsurprising thing about this is that students formed bonds based on shared interest, while the most intriguing repercussion is that the students took ownership of the spaces they used to discuss these topics, creating their own policies and terms of use. This helped several students later on in life when they were in the throes of a new peer group of people from different backgrounds and they needed to find ways to collaborate and learn together. Having had this experience during their Global Studies programmes, they were able to easily recall the things that worked and the things that didn’t which essentially gave them increased opportunities for leadership as well.

Listening to the students talk about their experiences and reflect on what they had learned while the world was thrust into a state of flux and disruption as a consequence of the pandemic was ultimately encouraging. I’m aware that the students taking part in this study do not reflect the experiences of the majority of young people around the world, and that the overall experience of online teaching and learning was subpar for most, appalling for many. Our modest contribution towards that experience started as an experiment, but through student engagement, enthusiasm and motivation, we were able to create something that had a lasting impact on many students.

This research project highlighted a number of pitfalls relating to what we taught across those two years, where I made assumptions about what students might know, underestimated tech capabilities across the board, and was deeply unprepared for taking on such large class sizes. However, as a consequence of this research, it feels as though there is solid ground for development and improvement in online learning as a continued vehicle for global competence development. I am better placed to design and develop a fresh curriculum (with input, no doubt, from some of the students who have helped with this research) and am energised by the possibilities that come with it. In spite of all that has changed with online teaching and learning since 2020, there is still a long way to go, but knowing that students report it can make an impact has to be a strong source of encouragement for all of us working in this area.