Student Leadership Groups with a Global Focus

Many GEBG Schools intend to equip students with the ability to lead in their lives beyond the school, and this goal is commonly manifested in student leadership groups or in opportunities for students to specialize in a particular area. For schools with a commitment to global education, it makes sense to provide students with the opportunity to hold both formal and informal leadership positions that celebrate the global objectives of the school and give students the opportunity to develop and facilitate global experiences for others within the community, near and far. However, many questions around structures, objectives, and capacity can make launching and sustaining one of these groups difficult, particularly given the other significant responsibilities of global directors.

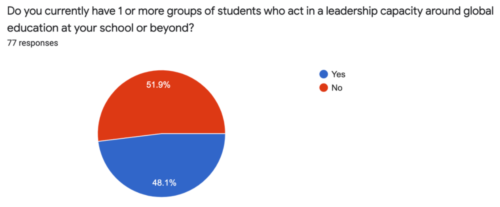

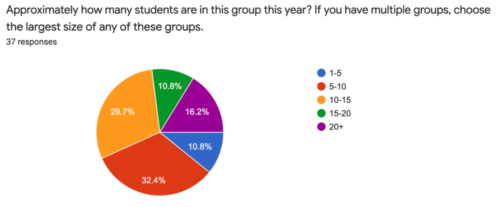

During a recent meet-up, leaders within the GEBG Community shared their current status with regard to these types of formalized leadership groups. Most schools in attendance that currently have leadership groups (37 total) include high school students (95%), and many fewer have groups at the middle school (19%) and primary school (3%) levels. Within these same schools, the majority have leadership groups of 5-10 (32%) or 10-15 (30%) students; about 11% have groups of 1-5 students, another 11% have 15-20 students, and 16% have groups larger than 20.

These differences in size often correlate with the objectives of the groups, and broadly, groups tend to fall into one of two categories: groups that focus on promoting global education through developing and facilitating events and opportunities, usually within the out-of-class context, and groups that consist of students following a path of specialization that includes coursework and often also global experiences in local, national, and/or global contexts. While these two models share many similar values, the collaborative and administrative demands of the adults involved can vary dramatically, as “global diploma” or “scholar” programs usually require engagement of many more adults within the school community to agree upon the elements of the specialization or certification and to provide the experiences necessary for a student to fulfill those requirements–from elective courses on global topics to community engagement or independent projects to travel programs, and usually have designated administrators and/or faculty.

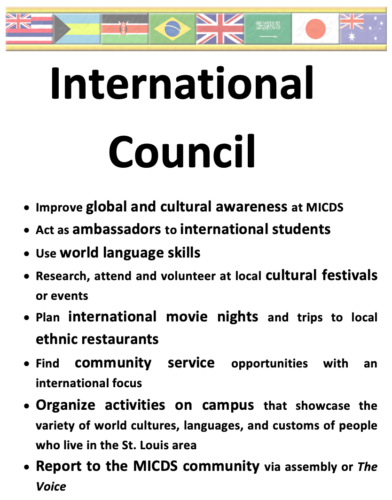

The names of these groups are diverse and often reflect the differences within their objectives:

|

|

Common group responsibilities include the following:

- Celebrating diverse cultures of the school community (62%)

- Promoting understanding of and engagement with global issues on campus (57%)

- Promoting intercultural understanding on campus (57%)

- Leading/supporting community engagement around global issues (57%)

- Developing on-campus/virtual global experiences for a larger group of students (i.e. events, dialogues, speakers, fundraisers, etc…) (54%)

- Collaborating with other student leadership organizations (43%)

- Working with outside organizations or partner schools (43%)

- Promoting/supporting travel experiences (41%)

- Leading/Participating in a global certificate/diploma program (30%)

- Leading an International Student Affinity Group (24%)

- Recruiting host families/supporting exchanges or international students (16%)

Also related is the process by which students apply to be a part of these leadership opportunities. 62% of participants in the meet-up with leadership groups require some type of application, and within these schools, the level of selectivity of the group usually correlates with the requirements of participation: leadership opportunities and programs with more individual requirements and high level of responsibility have a more stringent (and often more involved) selection process, and those with fewer and more shared responsibilities have less selective processes or no application process at all.

This year, the demand for this type of leadership has perhaps never been so clear, but schools continue to work through immediate challenges related to the pandemic. Schools that are successfully navigating these conflicting demands often direct the attention of the student leaders toward the pandemic by empowering students to engage with peers in virtual dialogues, to contribute to solutions in local contexts, and to sustain connections to other people and places through initiatives with international partner schools or domestic and local organizations. Utilizing the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a framework to both educate leaders on the issues and to focus their efforts in implementing solutions can help to manage the stress inherent to both leadership in a time of crisis and within a global context. Schools leaning into this opportunity are finding that students are eager to take on challenges that feel immediately relevant and important to their futures, resulting in greater levels of interest in some schools like Ursuline Academy in Texas and St. Andrew’s Episcopal in Mississippi.

As we look ahead, hopefully with many of the challenges of the pandemic behind us, opportunities to strengthen the quality of these types of global leadership opportunities arise:

- In these groups, to what extent are we teaching leadership versus simply providing opportunities to lead? To what extent are we articulating for all stakeholders what leadership learning outcomes or competencies these programs intend to help students achieve?

- To what extent are students being taught essential and contextualized knowledge around global issues or global communities alongside learning about how to take meaningful action that is empathy-based, sustainable, and developed in partnership with the community impacted?

- What more might we do to ensure that students and other community members perceive these positions as curricular offerings that explicitly, persistently, and coherently provide opportunities to practice the knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary to be a successful leader, both within and outside of explicitly global contexts?

- To what extent are we prioritizing and aligning necessary resources (time, faculty, funding, etc.) to reflect the critical importance of this type of leadership development program?

Global Scholars at Polytechnic School in California engage in a substantial program consisting of required coursework, leadership-development experiences, and a culminating project of personal and societal significance.