Virtual Exchange, an Essential Global Pedagogy with Timely Appeal

Although virtual exchange has been a valuable component of global education for many years now, remote-learning environments have brought new interest to the pedagogy. Last fall, the GEBG brought together K-5 educators from 17 different schools as part of a year-long virtual exchange cohort, and we recently completed a virtual exchange program that focused on the UN Sustainable Development Goals, convening nearly 150 students from across the US and Morocco to share experiences and collaborate across differences. Additionally, GEBG has been working with member schools to develop competency-driven virtual-exchange programs based on the schools’ unique missions and educational programs, including curriculum development and faculty training.

Throughout the development, facilitating, and reflection upon these programs; we have strengthened our understanding of some of the model practices in virtual exchange, and we have had the pleasure of working with and learning from numerous educators from around the world who are committing to this type of teaching and learning–and embracing it for both its opportunities and challenges. This article attempts to synthesize and distill these experiences to provide some guidance as you approach your own program development, all the while sharing perspectives from a few current practitioners within our community in addition to other resources.

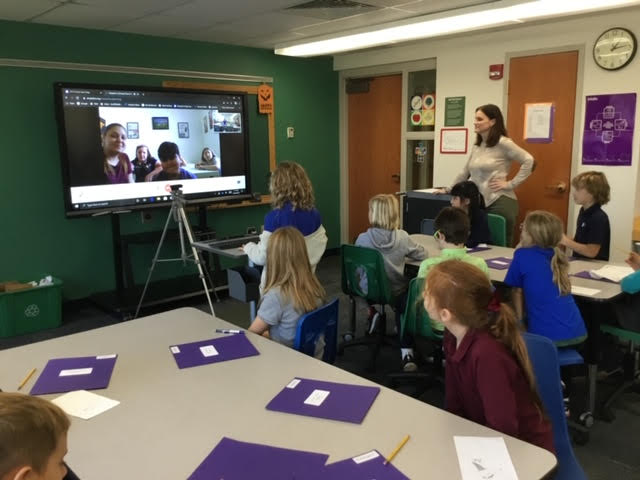

A 3rd-Grade Classroom at Old Trail School in Ohio exchanges with a partner in Brazil

What is Virtual Exchange?

The Stevens Initiative “is an international effort to build global competence for young people in the United States and the Middle East and North Africa by growing and enhancing the field of virtual exchange: online, international, and collaborative learning.” As one of the leading organizations supporting virtual exchange around the world, Stevens describes virtual exchange as “[u]sing technology to help young people learn about the world and about each other[,]…giving young people the knowledge, skills, and experiences they need to prosper in an interconnected world.”

They describe three key phases of the exchange:

- Educators and other facilitators work together to design collaborative learning programs

- Young people use a variety of technology tools to connect with each other in real-time and asynchronously over a sustained period

- Participants build global competencies and other skills and knowledge they need to participate in the workforce and in society

There are many educational benefits of using virtual exchange as a pedagogy: namely, it develops intercultural competencies–particularly communication and collaboration–and it allows teachers to connect with one another for the mutual benefit of their students as global citizens. While virtual exchange has provided a lifeline for travel programming stifled by COVID-19, it has also reminded us of its immense power as an extremely low-cost opportunity to bring communities near and far into the classroom to enrich it with diverse experiences and voices. As Stevens describes it, “[b]y combining technology with proven educational techniques, virtual exchanges make it possible for every young person to have access to a meaningful cross-cultural experience.”

A Few Common Misconceptions about Virtual Exchange

- Virtual exchange should–or even can–replace other ways of teaching and learning

- Virtual exchange is only a temporary substitute for superior, in-person programming

- Virtual exchange isn’t doable for the average teacher

- Virtual exchange must involve conversation with people who are from, live in, and/or currently reside in another country

One common misconception about virtual exchange is that it should–or even can–replace other ways of teaching and learning. Virtual exchange is one of many pedagogical approaches that can be added to a teacher’s array of practices, each with their own strengths and weaknesses. While COVID-19 has uncovered, for many, the opportunities that virtual exchange provides, it has always been a pedagogy with distinct ability to teach global competencies, particularly intercultural communication and collaboration across differences.

In addition, while virtual exchange cannot necessarily replace all aspects of in-person exchanges, it is not simply a temporary substitute for in-person learning; When utilized thoughtfully within an intentionally designed curriculum, virtual exchange can provide opportunities with greater access and even greater quality than in-personal programming often provides. While travel programs may be disconnected from classroom curriculum and accessible to only some of a school’s community members, virtual exchange is often more directly integrated into curriculum and more immediately accessible to students. Furthermore, global competencies that are taught through in-person programs often overlap in ways that can make observation of learning difficult, whereas virtual exchanges provide a more focused experience with competencies that might be easier to evaluate, for both teachers and participants. In that sense, virtual exchange is a tool worth investing in now for both its short- and long-term benefits.

Another misconception is that virtual exchange isn’t doable for the average teacher. While all virtual exchange requires thoughtful planning–like any curricular pedagogy–the time and energy that this preparation requires depends on the scope and scale of the program. For an exchange with complex educational outcomes that require a lot of practice, it is often best when all of the exchange partners have agreed to engage in virtual exchange long before the exchange begins, a scenario which provides the opportunity to develop a curriculum that is designed for the benefit of all student participants–and is based on trust and collaboration among the adults facilitating the program. At the same time, a single classroom teacher–with patience–can identify a partner through one of the many online resources available (some are included in links at the end of this article) and create multiple opportunities for their/her/his students to engage meaningfully with people in other places, and these experiences can be directly connected to learning targets that transcend the exchanges themselves. Additionally, some of the best virtual exchanges we have seen leverage preexisting school partnerships and networks to identify partners who already understand the objectives of the exchange and the shared goals of the schools’ and their students’ needs and desires.

One last misconception of note is that virtual exchange must involve conversation with people who are from, live in, and/or currently reside in another country. While there are clear and obvious benefits to the dialogues possible between two classrooms in two different countries, we know that intercultural exchanges happen every day; however, these exchanges among peers with different experiences and identities aren’t necessarily made the goal of student activities. (This is perhaps part of why we see students across the world today taking action, asking for more representation in curriculum and the elimination of bias and white supremacy in what they are–or aren’t–learning.) This year in our virtual exchange cohort we saw multiple examples of successful intercultural virtual exchanges that occurred between and among schools in the same country; what made them meaningful was that the design and facilitation created safe opportunities for students to share about their experiences and identities–and to then leverage those experiences and identities in collaborative, intercultural collaboration. Students with computers and private Zoom spaces worked in a project group with others who participated solely on phones without video; students in high school exchanged with 5th Graders; students whose second or third language is English presented alongside native speakers; and students who might not normally consider themselves agents of change took action alongside students who have felt empowered for years.

“[The students] were really surprised by the similarities between our two schools and equally enjoyed learning about some differences. My [partner] school is [also in the US], so the differences were not so big. I do think they realized some of the privileges that come from being in a private school and appreciated some of the things they take for granted more.”

–2nd Grade Teacher from K-5 Virtual Exchange Cohort

Students in Pasadena Poly’s Global Initiatives Program (GIP) cleverly utilize a combination of videoconferencing platforms to connect with partners in Langa Township, South Africa

Virtual Exchange Connects Across Many Differences

Jennifer Hayman, teacher at Severn School in Maryland, was initially hesitant when her 5th-Grade classroom was paired with an evening English class for high school students in Greece, “but it ended up being great.”

Jennifer explains: “Our first meeting was focused on just getting to know their pals. The students in both groups took turns asking questions about the location of the school and each others’ favorites such as favorite subjects, sports, foods, and pets. After the meeting, my students’ big takeaways were how much they had in common. Each week they kept asking when we were meeting again.

The timing of our second exchange corresponded with our global studies unit of how different winter holidays were celebrated around the world. My partner teacher and I had our classes prepare for the meeting by thinking about their family traditions, traditional meals that are served, and celebrations related to their particular religious beliefs. When we connected virtually the students shared what they had written. My partner teacher had sent me their typed responses ahead of time so that my students could follow along to the answers while our partner classes practiced their English; My students had a holiday sing along that afternoon and we ended the meeting with them singing their holiday song to their partner classmates.”

While Jennifer experienced challenges in sustaining communication through the online platform, the experience reaffirmed her commitment to virtual exchange: “With everything going on around the world, I believe connecting to other students and classrooms is even more important than it was last year. I plan on starting this fall finding another classroom match and making it work whether we are remote or not.”

Some Model Practices in Virtual Exchange

Personnel

- It is helpful to make distinctions between all of the various roles: for example, observer v. teacher v. facilitator or exchange participant v. virtual host sibling v. student discussion leader.

- If adults/leaders are expected to play multiple roles, it’s helpful if they can have practice/experience in all of those roles ahead of time (this impacts training and recruitment).

- Educators who have strong intercultural fluency and/or experience teaching students to navigate cross-cultural settings and communications (i.e. teachers who thoughtfully address difference and identity in their courses, anti-racist educators, and travel program leaders) have many skills that help in building and facilitating virtual exchanges: namely, preparation for exchange and debriefing, holding students accountable without using the threat of assessments, and guiding students through a process that’s both intellectual and emotional.

Curriculum Development

- Unstructured time needs to be put into the structure (faculty lounge, icebreakers, conversations that happen on and off program platforms, etc…); “debriefing” time needs to be set aside so that each constituent of the exchange has time to process the exchanges themselves, providing time for students to explore questions independently, for teachers to develop supplemental lessons or to provide resources that follow-up on topics or challenges that arise throughout the exchanges, and to ensure that the students’ intellectual AND interpersonal growth are being taken into account when evaluating their participation and the success of the program.

- Because there are fewer (and distinct) live, physical cues from students in virtual environments, teachers have to be more proactive in their planning, not only in terms of logistics (see below), but also in terms of their structural/curricular considerations of different learning styles, of students’ home circumstances, and of the reality that teachers may have to develop more and new ways of differentiating teaching, content, and checks for understanding beyond what they are used to in the classroom.

Pre-Exchange Planning

- Planning is always important, but there is more planning–or at least planning that focuses on more logistics–that needs to happen to make sure the exchange itself works; there is also more preparation and rehearsal in addition to debrief. (Think of it like a stage performance: lots of rehearsals for the performance, which always includes mistakes and adaptation, and what makes the process worth it is the way in which it leads to conversations/impressions/learning afterward, which is always strengthened when time is allocated and the discussion is facilitated, in some way.)

- There is a lot that goes into the development of the program, but the biggest indicators of success are 1) strong partnership between organizations with clear understanding of the purpose of the program, 2) appropriate numbers and skills/roles of adults to match the various cultures and communities from which students are coming (for exchange as well as accountability), and 3) students who are clear about the program goals and who have multiples sources of support throughout (including people checking in with them).

Participation and Engagement

- “Showing up” looks and feels different: there are ways to show that you are there and listening that don’t involve having video or sound on, and there is also greater importance on non-verbal forms of affirmation. Also, think about other types of communication and their integration into your program design (i.e. chat box, LMS, WhatsApp, etc…).

- While the curriculum should ideally include various, diverse ways of communicating student expectations, sharing knowledge, and asking for help; teachers and students need to also be aware that they may need to modify their own behaviors to help signal to others in the exchange that they are engaged and interested. Students may need to practice some of these non-verbal cues or to commit to a form of participating that may not be immediately natural (i.e. asking questions in a chat box instead of raising a hand); teachers may need to say and do more “up front” to signal to their students (and to those from exchange-partner schools whom the teachers might not know) that they are inclusive of various learning styles, understanding of different students’ home lives and access to resources, and accepting of technical challenges and other unfamiliar forms of student challenges that might not appear in the in-person classroom (i.e. not understanding someone’s accent or feeling misunderstood in a conversation about identity). Teachers unused to online teaching and learning may want to commit to multiple opportunities for sharing anonymous feedback throughout the process so that students and teachers can feel comfortable that everyone is on the same page about the purpose of the exchanges and expectations thereof.

Leadership and Facilitation (“The teachers are exchanging, too!”)

- Teachers have their own intercultural work to do and competency needs.

- It’s about the kids being together (not about the content).

- Giving students choice allows conversations to get to “the authentic” more quickly.

- Modeling flexibility and adaptability for all is of paramount importance.

- Using a shared topic or current issue is a great way to create a jumping-off point content-wise (i.e. COVID-19, student action, the notion of “home,” etc…).

- Communication and Collaboration are ever-present–for both the facilitators and the students. Everyone needs to be ready to commit.

- Debriefing is not optional–that’s often when the teacher and students can really investigate assumptions, unpack challenges, and set goals for improvement.

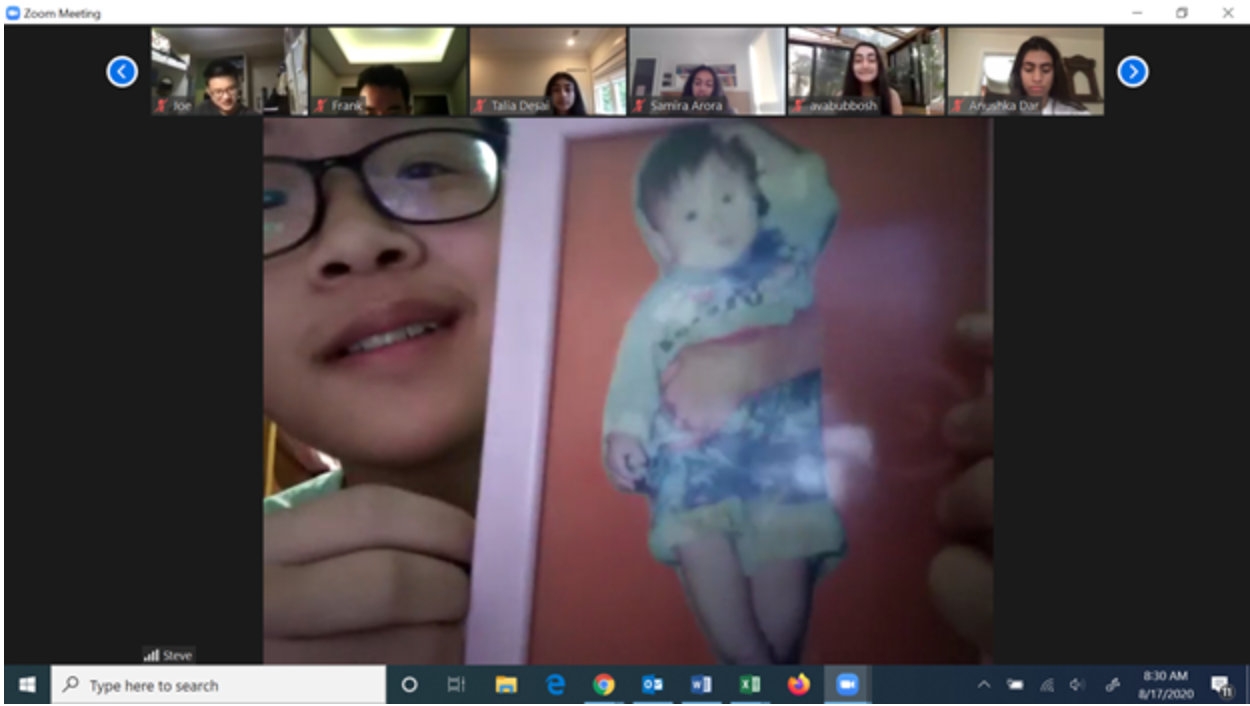

Students in Holton-Arms’ Junior Journeys Program 2020 share an artifact from “home”

Practitioner Perspectives and Sample Lessons from Holton-Arms’ Junior Journeys

At Holton-Arms School in Bethesda, Maryland; a team of 17 faculty and staff worked to adapt their “Junior Journeys” travel programs into virtual exchanges that utilized long-standing school partnerships in Peru and India and added a new partner in China; through the experience, the faculty realized the value that virtual exchanges possess in their own right and intend to sustain the virtual journeys even when the travel-based programs continue in the future.

“The most rewarding part of this experience has been to witness the curiosity and joy that takes shape as students from two different parts of the world come to understand each other to build meaningful and lasting relationships. It is essential to their development as global citizens seeking to build lasting peace and justice in the world. Although there are things that the virtual space cannot offer in the same way that travel can, what it does offer is the chance to interact academically with students abroad to closely examine global issues from various perspectives.

This virtual journey experience has been such a rewarding one. As we set forth the goals for this program, I never expected that I would embark upon a similar journey as my students. It has challenged me to examine, practice and develop my teaching skills as a collaborator and communicator, and further prepared me to provide a better educational experience for my students in the Fall.

We are hoping to continue our virtual programs as a staple part of the global education experience at our school. Not only can these programs offer a rich development of global competence and skill building, they provide a more equitable experience for students who are unable to participate in travel programs. Additionally, we hope that the curriculum and teaching tools can help other educators bring new concepts and ideas to their classrooms and further expand our capacity to incorporate a more global and diverse education to our students.

As is the case with most new programming, I wish we had more time for the planning and preparation. The best advice I could give, especially during these stressful and uncertain times, would be to be kind to yourself and allow room for the program and curriculum to take on a life of its own.”

–Kelly Randall, Assistant Director of Diversity, Wellbeing and Global Education (China Junior Journeys 2020 Facilitator), Holton-Arms, Bethesda, MD

Holton-Arms Faculty collaborate during a mid-program check-in

“With this program, there is a real exchange of knowledge; Our students are learning as much about their own country as the country they are exploring. In addition, the virtual experience allows students to connect face to face without a lot of distractions. They are really able to focus on building relationships. We are also really able to use our face to face time effectively. As teachers, we have experienced the same joy of getting to know and work with peers across the world.”

–Rachel Lowenthal, Upper School Science Teacher (Peru Junior Journeys 2020 Facilitator), Holton-Arms, Bethesda, MD

Two Lesson Plans from Holton-Arms’ Junior Journeys 2020

Felsted School in the UK utilized effective, varied communications to developed shared understanding around virtual summer opportunities for students from around the world

Re/imagining Global Education Programs

This year, Daniel Emmerson–Director of Global Education at Felsted School in Essex, England–had the distinct challenge of transforming a six-week summer school for students from around the world into a fully virtual program. The 2020 Program not only overcame logistical and technological hurdles, but it also excelled in utilizing effective communication strategies to share about the program and its value. Daniel explains:

“Our aim was to create a dynamic, virtual experience for students so that they could collaborate, learn and work together while engaging with other people from different backgrounds.

One of the central considerations we needed to make involved understanding cultural differences and how our students might respond to material, particularly for the global studies course. We also needed to consider access to technology, which was perhaps our main hurdle throughout the entire programme.

From a communications perspective, this meant regularly checking up on student wellbeing. We also needed to remind out students to be considerate and thoughtful when voicing opinions and sharing information. We were lucky to have such a highly motivated and conscientious group of students, who remained thoughtful and respectful throughout.”

Additional Resources

Virtual Exchange Resources (Stevens Initiative)

Dialogue Resources (Generation Global)

Difficult Dialogue (Teaching Tolerance)

GEBG Global Partnership Framework

“For me, it was really interesting to see how to set up a full-scale virtual class experience using multiple platforms. I also loved getting the opportunity to watch my students grow as a result of being tasked with a leadership project. They had to really stretch their skills muscles – esp. communication, taking initiative, collaborating, while also responsible for doing independent research, and being able to be flexible.”

–Faculty advisor in SDG Virtual Exchange Program

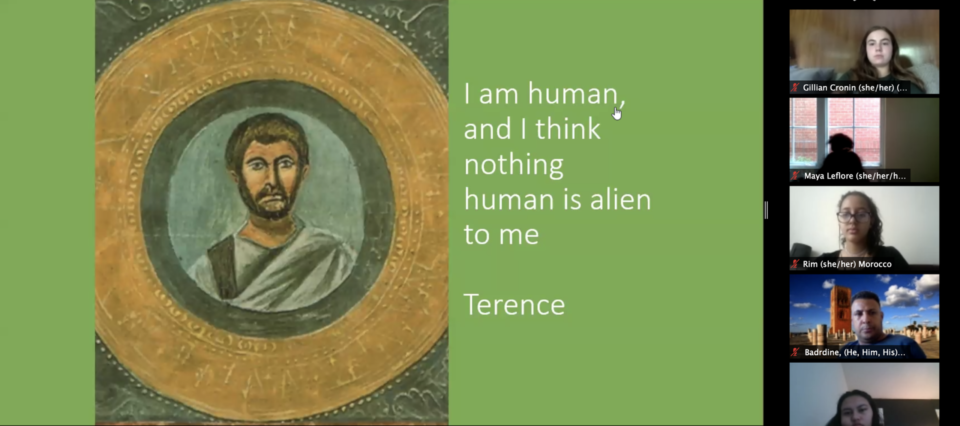

Educators from across the US and Morocco meet during a weekly “faculty lounge” meeting–part of the GEBG SDG Virtual Exchange Program–to reflect on their students’ experiences and how to apply this work in their own schools and classrooms